More Stories

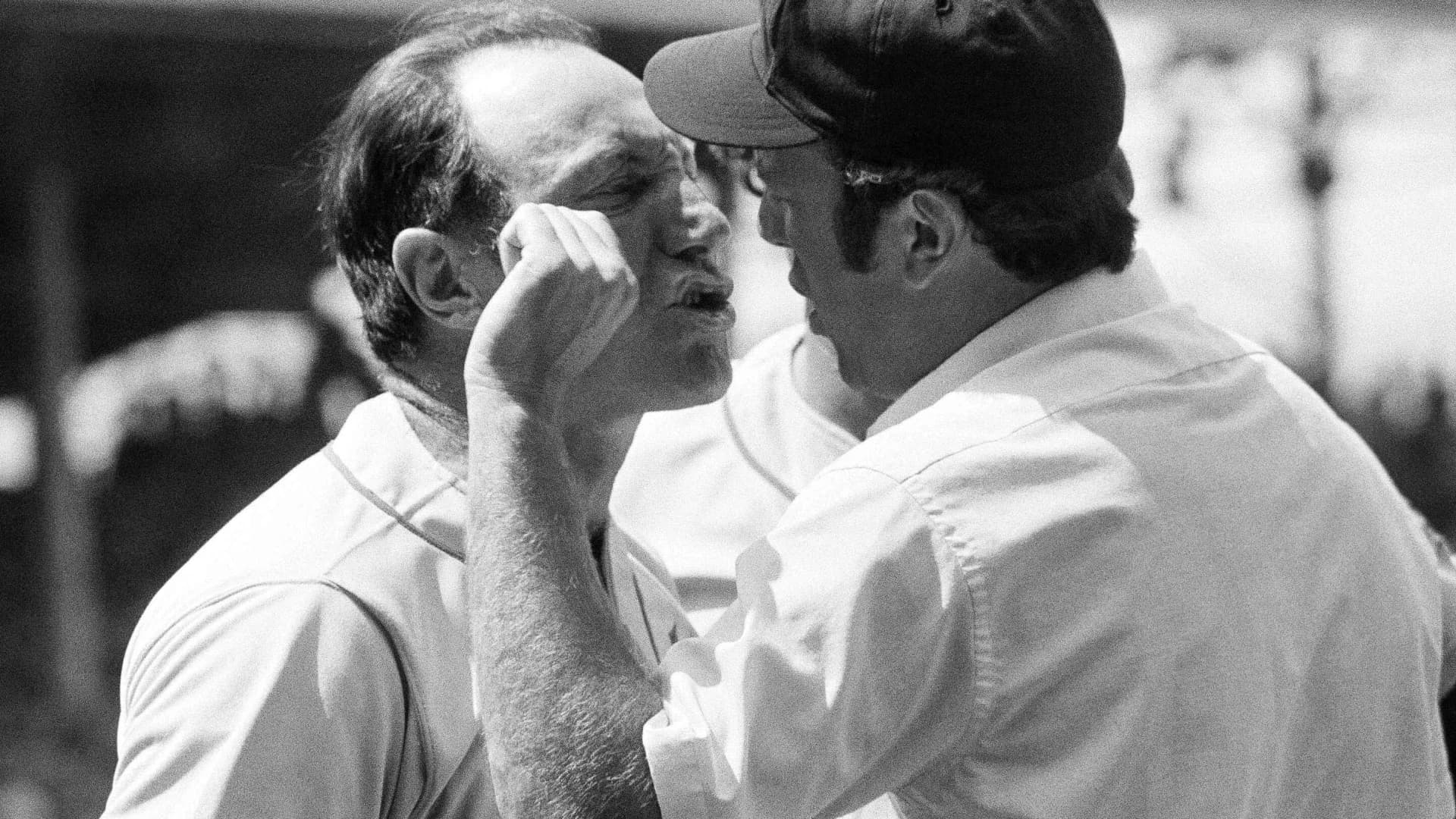

As a big leaguer,

Joe Pignatano had a career that was more noteworthy than notable: He

played in the last game at Ebbets Field, he homered off three future

Hall of Famers and he hit into a triple play with his final swing in the

majors.

It was

out in the bullpen at Shea Stadium, where he tended relief pitchers and

tomatoes for the 1969 Miracle Mets, where Pignatano’s legacy really

grew.

“He was fairly committed to taking care of his tomatoes,” former Mets pitcher Jim McAndrew told The Associated Press.

“It was Joe’s thing,” he said. “A lot of love and effort and TLC.”

Pignatano,

who reached the majors as a catcher with his hometown Brooklyn Dodgers

and became a longtime coach, died Monday at 92.

The New York Mets said Pignatano died in Naples, Florida, at a nursing home. He had been suffering from dementia.

Pignatano

had been the last living coach from the 1969 Mets, who made a

remarkable run under manager Gil Hodges to reach the World Series and

then startled Baltimore and the baseball world for their first

championship.

He remained as their bullpen coach through 1981.

“To

me, he was Uncle Joe. He loved the city and loved talking about his

days with the Dodgers and with Gil. He was a baseball lifer,” former

Mets star Lee Mazzilli said.

Pignatano

made his major league debut with Brooklyn in 1957. On Sept. 24, he took

over for future Hall of Famer Roy Campanella and caught the final five

innings in a 2-0 win over Pittsburgh. It was the Dodgers’ last home game

before bolting Brooklyn for the West Coast.

In

1959, Pignatano got his biggest hit. In the second game in a

best-of-three playoff against Milwaukee for the NL pennant, his two-out

single in the bottom of the 12th at the Coliseum set up the winning run

scored by Hodges as Los Angeles earned a World Series spot.

The

Dodgers went on to win the championship, and Pignatano had a brief

appearance behind the plate in the six-game win over the Chicago White

Sox.

After

stints with the Kansas City Athletics and San Francisco Giants, he

joined the 1962 expansion Mets in midseason. The Mets were awful,

setting a modern major league record for losses in going 40-120, and

they wrapped up their season in inglorious fashion.

In

their final game of the season, at Wrigley Field against the Cubs, they

trailed 5-1 when Sammy Drake led off the eighth inning with a single

and took second on a single by Richie Ashburn.

Pignatano

was up next and sent a liner toward right field — “that ball was

labeled base hit from the moment it left the bat” is how it was

described on Mets radio.

Instead,

Chicago second baseman Ken Hubbs went back and caught the ball and

threw to first baseman Ernie Banks, who relayed to shortstop Andre

Rodgers for a triple play.

It was Pignatano’s last at-bat in the majors.

A

career .234 hitter, he played 307 games and hit 16 home runs. Among the

pitchers he tagged for homers were Robin Roberts, Warren Spahn and Jim

Kaat, all of them Hall of Famers.

In

1965, Hodges was managing the Washington Senators when he asked

Pignatano to join his coaching staff. In 1968, Pignatano went with

Hodges to the Mets.

During

the 1969 season, Pignatano discovered a stray tomato plant growing in

the right field bullpen at Shea and kept it healthy. As the Mets

continued to win, the plant became something of a good-luck charm and

Pignatano’s garden took root.

“It

was his home away from home,” McAndrew recalled Monday. “He had five or

six hours a day down there with his tomatoes. He really took care of

them. When we were on the road, the grounds crew helped out. They had

the water.”

Over

the years, the ripe, red tomatoes grew and so did the stories about

Pignatano’s green thumb. He was always glad to talk about his garden.

But letting others enjoy his harvest? Nope, McAndrew said he never got to taste a single juicy tomato.

“He didn’t share them. They were just for him,” McAndrew said with a laugh. “He was going to reap the fruits of his bounty.”

By BEN WALKER

AP Photo/Larry Stoddard

More from News 12

1:42

NYPD searches for 2 men wanted for robbing, stabbing man in Bedford Park

2:21

STORM WATCH: Late-night mix gives way to sloppy Tuesday commute for The Bronx

0:25

Mamdani appoints a former FTC director to lead Dept. of Consumer and Worker Protection

4:17

‘Why don’t we have any answers?’ Bronx family demands justice in decades old cold case

1:51

City Council passes bill to finance affordable housing for families

1:46